High-Leverage Practices and Evidence-Based Practices: A Promising Pair

Erica D. McCray, Margaret Kamman, Mary T. Brownell

University of Florida

Suzanne Robinson

University of Kansas

High-leverage practices (HLPs) and evidence-based practices (EBPs) when used together can

become powerful tools for improving student outcomes. This brief is designed to show the promise

of these practices in advancing educator preparation and practice and, subsequently, outcomes for

students with disabilities and those who struggle. We begin by defining HLPs and EBPs and sharing

examples of how educator preparation programs are integrating them in their candidates’ learning

opportunities and conclude with an illustration of how they can be seamlessly integrated into

instruction provided as part of multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS).

High-Leverage Practices: What Are They and Why Are They Important?

Educator preparation programs have come under sharp criticism in recent years for failing to

demonstrate the impact of their graduates on the achievement of their students. Teachers and

leaders are key to improving outcomes of students with disabilities. Preparation experiences must

include well-supervised opportunities for candidates to practice with feedback about what they are

learning in coursework. Field placements should be carefully selected to reinforce what candidates

have learned in coursework. To move in the direction of tightly structured learning opportunities

for teacher candidates, scholars in general and special education (Ball & Forzani, 2011; McLeskey

& Brownell, 2015) have argued that teacher educators need to identify a critical set of practices

that are essential to improving student learning and behavior and can be learned in coursework,

deliberately practiced in field experiences carefully structured by faculty (e.g., tutoring small groups

of students in identified practices), and generalized to more loosely structured field experiences.

These critical practices, also known HLPs, should be those that research has demonstrated can

impact student achievement and be used across different content areas and grade levels. These

HLPs should also be those that teacher candidates can learn through practice and feedback. They

would form a “common core of professional knowledge and skill that can be taught to aspiring

teachers across all types of programs and pathways” (Ball & Forzani, 2011, p. 19). HLPs can provide

infrastructure to support effective teaching and consistent learning for every student to succeed.

Specialized Practices

To extend the HLPs that Deborah Ball and her colleagues developed for special education, the

CEEDAR Center, the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC), and the Teacher Education Division

of CEC supported a group of experts to generate HLPs for special education teachers in grades

K-12. This High-Leverage Practices Writing Team developed HLPs in four domains: (a) collaboration,

(b) assessment, (c) social/emotional and behavioral support, and (d) instruction (see below). The

identified HLPs were supported by research on student learning or policy/legal foundations in the

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

HLPs for Special Education

Collaboration

- Collaborate with professionals to increase student success

- Organize and facilitate effective meetings with professionals and families

- Collaborate with families to support student learning and secure needed services

Assessment

- Use multiple sources of information to develop a comprehensive understanding of a student’s strengths and needs

- Interpret and communicate assessment information with stakeholders to collaboratively design and implement educational programs

- Use student assessment, analyze instructional practices, and make necessary adjustments that improve student outcomes

Social/Emotional and Behavioral Support

- Establish a consistent, organized, and respectful learning environment

- Provide positive and constructive feedback to guide students’ learning and behavior

- Teach social behaviors

- Conduct functional behavioral assessments to develop individual student behavior support plans

Instruction

- Identify and prioritize long- and short-term learning goals

- Systematically design instruction toward a specific goal

- Adapt curriculum tasks and materials for specific learning goals

- Teach cognitive and metacognitive strategies to support learning and independence

- Provide scaffolded supports

- Use explicit instruction

- Use flexible grouping

- Use strategies to promote active student engagement

- Use assistive and instructional technologies

- Provide intensive instruction

- Teach students to maintain and generalize new learning across time and settings

- Provide positive and constructive feedback to guide students’ learning and behavior

Resources: Practice-Based Opportunities and High-Leverage Practices in General and Special Education

Practice-Based Opportunities Brief: outlines essential features for providing high-quality, structured, and sequenced opportunities to practice within teacher preparation programs.

CEEDAR HLP Review: identifies the need to identify high-leverage practices unique to special education.

High-Leverage Practices: describes high-leverage practices for general education.

High-Leverage Practices in Special Education: outlines high leverage practices in special education.

McLeskey and Brownell (2015) noted that (a) many of the general HLPs are appropriate for all

teachers, and (b) many of the HLPs identified for special education vary only in intensity and focus.

Table 1 illustrates commonalities and distinctions across the two sets of HLPs. Understanding the

increasingly intensified practices needed as special and general education teachers teach students

with disabilities is important.

Table 1. Commonalities and Distinctions Across HLPs

| High-Leverage Practices (from Teaching Works) | High-Leverage Practices in Special Education |

|---|---|

| Explaining and modeling content, practices, and strategies |

|

| Diagnosing particular common patterns of student thinking and development in a subject-matter domain |

|

| Coordinating and adjusting instruction during a lesson |

|

| Setting up and managing small-group work |

|

| Specifying and reinforcing productive student behavior |

|

Evidence-Based Practices: What Are They and Why Are They Important?

EBPs for special education are instructional strategies backed by research and professional expertise to support the learning and behavior of students with disabilities (Cook, Tankersley, & Harjusola-Webb, 2008). EBPs are often content focused and appropriate for students at different developmental levels. For instance, teaching students strategies for summarizing text is a powerful strategy, but the strategy is best taught in third grade and beyond.

At the CEEDAR Center, experts have identified the evidence in specific content areas (e.g., reading, writing, mathematics, behavior). These EBPs are described in innovation configurations (ICs) available on the CEEDAR Center’s website. Faculty can use these ICs to determine the extent to which their programs are providing teacher candidates opportunities to learn and practice the most critical EBPs—some of which are also considered HLPs.

HLPs and EBPs: A Promising Pair

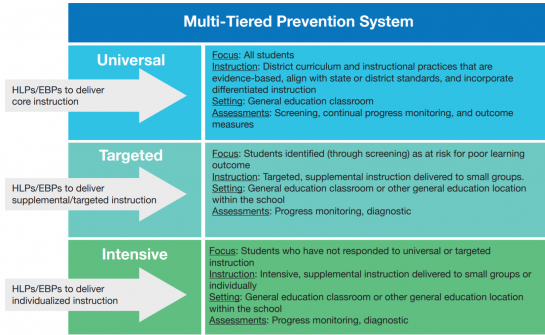

Many states and districts are implementing MTSS to increase the success of all students. MTSS is a

framework for instruction that focuses on prevention and intervention. All students receive evidence based instruction in core (or Tier 1) curriculum and increasingly specialized instruction (Tier 2) with

intensive and individualized intervention (Tier 3) as needed (see Figure 1). HLPs and EBPs are ideal

complementary practices for implementing MTSS. HLPs can be used to teach EBPs in specific

content areas.

*Figure adapted from www.rti4success.org

Grand Valley State University (Michigan) Example

Grand Valley State University (GVSU) in Michigan has been working to embed HLPs for general and special education into their educator preparation programs. The faculty believe that all beginning teachers should be prepared to teach all learners on day one. This initiative addresses an educator equity issue—all children deserve a skilled teacher. Historically, districts and universities speak about instruction in vague terms. HLPs provide precision and focus to teaching and the expectations for teachers. GVSU just completed its first year of a professional learning community (PLC), which included their faculty and field coordinators and cooperating teachers and teacher leaders from the partnering district. The group collaborated to accomplish several goals.

First, they analyzed the HLPs in general and special education to unpack the terms and practices. Then, the group tackled the pedagogy of teaching HLPs to teacher candidates and beginning teachers. The PLC developed common language and understanding, which was lacking prior to establishing the PLC. The PLC provided a structure for agreeing on and institutionalizing HLPs for teacher candidates and beginning teachers and streamlining their roles as teacher educators at the pre- and in-service levels.

Figure 1. Multi-Level Prevention System

A Case Example: How to Integrate HLPs and EBPs

The following case example illustrates reading instruction using HLPs (see bold text below) and EBPs (see italicized, underlined text below) for Reading K-5 (Lane, 2014) and Writing Instruction (Troia, 2014) across tiers. Specific examples are included below:

High-Leverage Practices

- Teach cognitive and metacognitive strategies (HLP14)

- Scaffold supports (HLP15)

- Use instructional technology (HLP19)

- Use active student engagement (HLP18)

- Use flexible grouping (HLP17)

- Provide positive feedback (HLP22)

- Provide explicit instruction (HLP16)

- Provide intensive instruction (HLP20)

- Adapt curriculum tasks (HLP13)

Evidence-Based Practices

- Provide vocabulary instruction (RP6.6)

- Teach making inferences (RP7.5)

- Teach modeling (RP7.6)

- Teach paraphrasing (RP7.3)

- Teach process: Outlining (W2.1)

Tier 1: Universal

A third-grade teacher, Ms. Lexicon, has planned a lesson to provide opportunities to practice writing skills with a complementary focus on expanding students’ use of sophisticated vocabulary words. The lesson begins with Ms. L reading a passage to the class while displaying the text on the Smartboard. First, Ms. L uses explicit instruction and Text Talk (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2013), an evidence-based strategy, to help students understand what a vivid verb is and why it is important to use when writing. Students are then prompted to look and listen for vivid verbs as she reads. After Ms. L completes the passage, she asks students to identify the vivid verbs and infer meaning. As the class discusses the sophisticated words, Ms. L asks them to think about how they might use those words, making linkages to familiar words, in their own stories later in the day.

Tier 2: Supplementary

Ms. Lexicon has identified a group of students who need targeted supplemental instruction. Ms. L uses flexible grouping to model thinking about a vivid vocabulary word. First, Ms. L and the group chorally read a portion of the text. Then, Ms. L focuses the students on one word: “blurting.” She allows for active student engagement by pausing and asking students what they think it means when a word is blurted out. As students provide answers, Ms. L provides positive feedback. After students tell what blurting means, Ms. L states explicitly that if the author used the word “said” instead of “blurting,” the reader could not visualize the interruption. She then tasks the group to practice locating vivid vocabulary by independently reading the remainder of the text and identifying vivid vocabulary, just as they did as a group.

Tier 3: Intensive

Ms. Lexicon was certain that one of her Tier 3 students, Adam, would need more intensive support beyond the small-group instruction. When she dismissed the group to continue reading independently, she asked Adam to stay with her for more explicit instruction. Ms. L provided more modeling by reading the passage aloud to Adam. Then, she segmented the passage into shorter chunks for Adam to read to her. Ms. L had Adam summarize the segments in his own words and write down his ideas and vocabulary words. This intentional discussion ensured Adam had an outline prepared for the writing assignment later in the day.

As the case example demonstrates, the coupling of HLPs and EBPs can be powerful when providing increasingly intensive instruction and intervention for students with disabilities and those who struggle. Using these practices for effectively implementing MTSS has the potential to transform teaching and learning to ensure that every student succeeds.

To improve outcomes for students with disabilities and those who struggle, teachers must be equipped with knowledge and skill that they can consistently use to meet the variety of needs that their students present. HLPs and EBPs show great promise when implemented well and can be a solid foundation for educator preparation programming in general and special education.

Questions about CEEDAR tools and resources?

Please contact the CEEDAR Center at http://www.ceedar.org

References

Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2011, Summer). Building a common core for learning to teach and connecting professional learning to practice. American Educator, 17-21, 38-39.

Beck, I., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Cook, B. G., Tankersely, M., & Harjusola-Webb, S. (2008). Evidence-based special education and professional wisdom: Putting it all together. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(2), 105-111.

Lane, H. (2014). Evidence-based reading instruction for grades K-5 (Document No. IC-12). Retrieved from University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability, and Reform Center website: http://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/tools/innovation-configurations/

McLeskey, J., & Brownell, M. (2015). High-leverage practices and teacher preparation in special education (Document No. PR-1). Retrieved from University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability, and Reform Center website: http://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/tools/best-practice-review/

Troia, G. (2014). Evidence-based practices for writing instruction (Document No. IC-5). Retrieved from University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability, and Reform Center website: http://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/tools/innovation-configuration/

This content was produced under U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, Award No. H325A120003. Bonnie Jones and David Guardino serve as the project officers. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Education. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, service, or enterprise mentioned in this content is intended or should be inferred.